on Ending

As this newsletter closes, an admittedly biased assessment of the industry’s pursuit of ACES and related observations. . . .

To Explain

The end. (Image: Ford)

This is the last edition of “on Automotive,” as I leave Gardner Business Media, which has been my journalistic home for more than 35 years. During this time I’ve had the opportunity—and honor—to work on Production Magazine, Automotive Production, Automotive Manufacturing and Production, Automotive Design and Production, and AutoBeat, all with first-rate colleagues on the editorial, business and managerial sides of the house (and the latter, I’ve got to say, gave me considerable latitude over the years, sometimes grudgingly and sometimes happily, but always respectfully: and I am certainly grateful for that).

I’ve had the opportunity to meet and learn from people in a variety of industries, from machine tools to robots, from automation to ADAS. And yes, of course, many of the women and men who design, engineer, produce, manage, and market vehicles.

While the “day job” comes to an end, this doesn’t mean I will stop covering the industry. I will continue to co-host “Autoline After Hours” and post at my site, shinymetalboxes.net. And who knows what else?

When I talk with colleagues covering auto who are similarly aged they say, to a person, that they want to stay in it because “This is the most exciting time in the auto industry in 100 years.”

Actually, that phrase isn’t entirely accurate because in the 1920s the industry was in a phase of regularization, not innovation. It was pretty much decided that there would be an engine under the hood, and the engine would be powered by gasoline. There would be steering wheels inside cabins. Steel became the material of choice. The assembly line was 10 years old by 1923. Alfred Sloan became the president of General Motors, which gave rise to the ladder structure that continues today (“a car for every purse and purpose”).

But let’s face it: to say “This is the most exciting time in the auto industry in 110 years” just doesn’t have the same impact.

What is particularly interesting about today is that there are changes occurring both organizationally and technically: who would have ever imagined that a company like Tesla—established in 2003—would become the automotive behemoth it is today, a company that has radically changed the ways vehicles are manufactured and marketed? Who would have imagined that companies that were around in 1923 (as well as some established since) would be aggressively chasing Tesla (and one could argue not doing a particularly good job at closing the gap)?

The acronym that is meant to encompass where the industry is focusing—for better or worse—right now is “ACES.” That’s for Automated, Connected, Electric, Shared.

So how’s this working out?

Automated

In 2017 Ford announced a test program with Domino’s Pizza in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Oddly, the Ford Fusion Hybrid Autonomous Research Vehicle was manually driven by a Ford safety engineer and there were researchers on board, so there were clearly more people to tip than in the non-autonomous arrangement. (Image: Ford)

Is this answering a question that no one is asking? Well, that depends who you ask.

Ford announced in 2016 that by 2021 it intended to have “a high-volume, fully autonomous SAE level 4-capable vehicle in commercial operation in 2021 in a ride-hailing or ride-sharing service.”

The key adjectives are “high-volume” and “commercial.”

In 2016 Argo AI, a company created for the development of autonomous driving tech, was established. It had a $1-billion investment from Ford. In 2019 Volkswagen joined with Ford with an investment in money--$1-billion—and $1.6-billion by adding its Autonomous Intelligent Driving company into the mix. Two of the technically most capable OEMs I the world were going in big on autonomous driving tech.

But in October 2022 they didn’t see a path forward, so the whole thing was dissolved. 2021 had come and gone with no high-volume, commercial autonomous ride hailing from them. (Ford created a subsidiary last March, Latitude AI, presumably figuring it has to keep its hand in the game.)

There was no “high-volume, fully autonomous SAE level-4 capable vehicle in commercial operation in 2021 in a ride-hailing or ride-sharing service” from Ford. Nor in 2023.

“High-volume” is something that just hasn’t happened

Meanwhile, GM’s Cruise AI, which the OEM has owned since 2016, has lost some $8-billion since then. It has also lost its ability—weeks after achieving it—to have its self-driving vehicles operating in California due to a horrendous accident involving one of its vehicles in San Francisco in early October.

In late November GM CEO Mary Barra, talking about Cruise, told investors “spending will be substantially lower in 2024 than it was in 2023.”

Still, the corporation has a commitment to Cruise.

In early December, during an Automotive Press Association meeting in Detroit, Barra characterized the $8-billion loss as an “investment.”

GM had earlier claimed that by 2030 Cruise could generate $50 billion per year in revenue.

Given what’s occurred in this space in general, not just at Cruise, that is something that can be described as a “stretch goal.” A long stretch.

And there’s more. According to a fact sheet developed by the University of Michigan’s Center for Sustainable Systems:

“There are several limitations and barriers that could impede adoption of AVs, including: the need for sufficient consumer demand, assurance of data security, protection against cyberattacks, regulations compatible with driverless operation, resolved liability laws, societal attitude and behavior change regarding distrust and subsequent resistance to AV use, and the development of economically viable AV technologies.”

Yes, lots of things to address and resolve.

Having an array of sensors and processors on vehicles that provide the abilities of Ford’s BlueCruise and GM’s Super Cruise—both Level 2+ systems—are useful. But is there truly more than isolated demand for Level 4 driving abilities?

That’s the question that needs an answer.

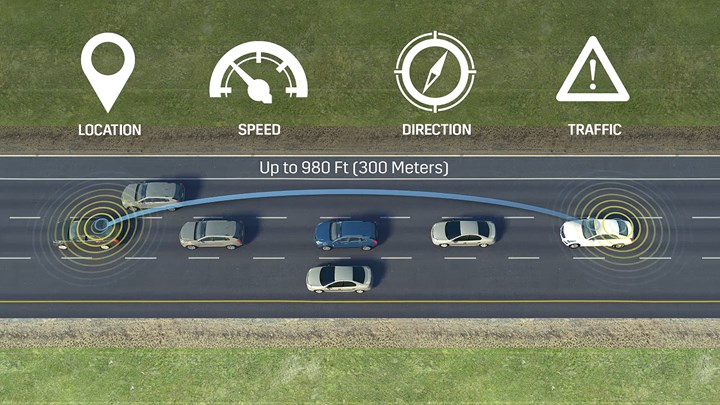

Connected

Cadillac, in 2017, announced it was installing V2V communications tech in its CTS sedans. Of course, the benefit of V2V tech is based on an array of vehicles being so equipped, otherwise there isn’t a whole lot of use. Cadillac, incidentally, stopped building the CTS in 2019. (Image: Cadillac)

This is the one that is curious. Essentially, a given vehicle is “connected” to other vehicles (V2V) and infrastructure (V2X) through a communications protocol. A vehicle would broadcast information about its condition such that if it was stalled around a curve, vehicles behind it would be aware of it and could slow down even though the drivers in those other vehicles wouldn’t be aware of the potential hazard.

And the V2X part of this could be as simple as a vehicle “knowing” when a traffic signal was going to change—or a traffic signal could “decide” not to change because it would “know” that vehicles weren’t coming from the cross direction. Smoother driving for everyone.

In January 2017 the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) proposed a Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard that light vehicles would be equipped with V2V capability. It pulled the proposal last month, citing “new V2V communications protocol” and “a recent Federal Communications Commission (FCC) decision regarding the regulations governing the 5.850–5.895 gigahertz (5.9 GHz) band.”

One imagines that were there to be bullish support on behalf of the OEMs there would be V2V and all of this discussion of bandwidths would be worked out. But while it is functional, it isn’t particularly sexy like self-driving vehicles are perceived to be.

This could be an example of the best being the enemy of the good—were it that the best (autonomy) actually had some widespread potential sooner rather than (considerably) later.

Electric

One of the things that people sometimes say about Tesla is that it is like Apple in terms of customers perceiving it as something worth paying more for compared with traditional products. (Remember when IBM was going to crush Apple in PCs?) Like Apple’s success in creating the iTunes infrastructure, Tesla built the Supercharger network: an advantage for getting people to buy the hardware to get a better experience (musically; electrically). (Image: Tesla)

There are two things at play. One is regulation. The other is market demand. So far there seems to be little in the way of intersection, at least in the United States.

When Motor Trend, in the fall of 2012, named the Tesla Model S the Car of the Year, things shifted. Not only was this the first electric vehicle that MT had selected for that honor, but think about it: Tesla was founded in 2003 and it built a car that outperformed contenders including the BMW 3 Series, Cadillac ATS, Mercedes SL, and Porsche 911 in an exceedingly short period of time.

And Tesla hasn’t looked back since.

The market demand for its vehicles has pretty much gone sharply up.

Slowly and sporadically other OEMs have followed with EVs.

But then the California Air Resources Board became more demanding regarding what was coming out of the tailpipes of vehicles, so the other OEMs had to become more serious after they had their “compliance car” play (i.e., putting mediocre EVs on the road that checked the box to meet California regs).

This past April the U.S. EPA came out with a proposed rule for light- and medium-duty vehicles staring in model year 2027. If the rule goes from a consideration to being on the books, it would require, in effect, that 67% of all passenger cars, trucks and SUVs being sold in the U.S. be EVs. By 2032.

So companies that want to sell vehicles in the U.S. would have to be really serious about an EV portfolio.

Given that Tesla is a company founded and based in the U.S. one might imagine that other auto companies in the U.S. would have the same sort of capabilities and be able to create the same sort of products that Tesla has on offer. But so far, that’s not the case.

Meanwhile, over in China and western Europe, EVs are taking off at a considerable pace. In the case of the former, much of this was predicated on government inducement. In the case of the latter, there seems to be greater environmental sensitivity among regular folk, and there is certainly an awareness of the greater price—by far—of gasoline compared to the U.S.

While there are seemingly headlines galore about some increase in EV sales, it is worth noting that according to the U.S. Department of Energy, which complied numbers of light-duty vehicle sales, in 2022 there were 2,442,300 EVs registered in the U.S. and 7,156,900. . .diesels.

This is not to say that EVs aren’t going to rise, but one really needs to be realistic about this whole thing. And to consider the role that government is playing.

The U.S. government not only wants to have a stick (EPA regs) to drive EV creation by the OEMs, but also a carrot for those in the market, which takes the primary form of the Inflation Reduction Act. Consumers can get up to $7,500 in a tax credit.

And manufacturers of batteries can get tax credits amounting to $35 a kilowatt hour (kWh) for battery cell production and an additional $10 kWh for battery modules. What’s more, there’s a 10% credit on costs associated with mining and processing materials for the batteries.

On December 1 the U.S. Department of the Treasury noted, “Since the IRA was enacted [August 16, 2022], nearly $100 billion in private-sector investment has been announced across the U.S. clean vehicle and battery supply chain.” Those credits are awfully appealing, apparently, because those investments aren’t being made in such abundance simply because the companies think they’re going to get an ROI from building batteries absent the monies from the government.

Here’s a question bringing us back to the top of this: Does the market want EVs or is this a function of incentives, to the individual consumer, as well as to the OEMs (with part of the OEMs’ incentives taking the form of having to meet the regs and another the money associated with battery production—and know they’re not getting that for building gasoline engines)?

Do people want to buy electric vehicles—or do they want to buy a Tesla?

Shared

The future of shared vehicles will be, more or less, rectangular, like this, the Cruise Origin. For one thing, the tech is expensive (and is likely to remain that way for a while), so being able to carry more passengers and move them in and out quickly and efficiently is necessary. (Image: Cruise)

Speaking of Elon Musk, in his “Master Plan, Part Deux,” posted in mid-2016, he wrote:

“When true self-driving is approved by regulators, it will mean that you will be able to summon your Tesla from pretty much anywhere. . . .You will also be able to add your car to the Tesla shared fleet just by tapping a button on the Tesla phone app and have it generate income for you while you're at work or on vacation, significantly offsetting and at times potentially exceeding the monthly loan or lease cost. This dramatically lowers the true cost of ownership to the point where almost anyone could own a Tesla. Since most cars are only in use by their owner for 5% to 10% of the day, the fundamental economic utility of a true self-driving car is likely to be several times that of a car which is not.”

That estimate of a vehicle being parked for 90% to 95% of the time isn’t just referring to Teslas. The thing that you spend tens of thousands of dollars on you drive, on average, 61.3 minutes per day. Which means it is not in use for nearly 23 hours.

(Fun fact for context: According to Nielsen, the average American spends 4 hours and three minutes per day watching TV.)

In 2019 Musk said, “I feel very confident predicting autonomous robotaxis for Tesla next year.”

Last year during his Q1 earnings call he said there would be volume production of a purpose-built Tesla robotaxi.

And this past May in an interview with CNBC he reiterated the economic benefits that can accrue from the people using their Teslas as robotaxis, which they still can’t.

But sharing doesn’t necessarily mean this is something that needs to be done autonomously, which is proving to be vexing.

Sharing is also related to ride hailing, like Lyft and Uber, and while those companies took a heavy hit when COVID arrived, there has been recovery by both companies.

According to McKinsey estimates, because of alternatives to private vehicle ownership (a.k.a., “mobility,” including sharing and ride-hailing (as well as scooters and bikes and. . .)), “In 2035, for example, car sales in the European Union are forecasted to be almost 20 percent lower than 2015 levels, and the United States could experience an even greater drop of 30 percent.”

Thirty percent. A huge hit to an industry predicated on volume (although given average transaction prices of late, one could argue that volume is now in second place to margins—by some distance). All because of transportation alternatives, including sharing.

Clearly, the impact of changes in modes of mobility are going to have profound consequences on the industry.

One of the creditable and credible things that Cruise has done is develop the Origin (with the assistance of Honda, as well as parent GM), a vehicle purpose-built for carrying six passengers. While there’s lots of attention to the fact that there’s no steering wheel or pedals, similarly notable is the functionality of the design for ingress and egress: people can move in and out quickly, thereby minimizing load/unload time. (While Cruise announced last week that due to the restructuring predicated on a horrible accident in San Francisco that it is “ceasing work on the Origin MY24” and focusing on the Chevy Bolt platform, ergonomically the Origin makes better sense.)

If shared is going to become as big as predicted, then there is going to need to be more Origin-like vehicles, regardless of their propulsion system and piloting approach.

///

Coda

An exciting time. But a challenging one.

Let me end with two quotes from Henry Ford, which seems apropos for an automotive newsletter.

The first quote is something that I hope leaders at OEM companies keep in mind as they are aggressively chasing ACES:

“I will build a motor car for the great multitude...constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise...so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one-and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God's great open spaces.”

To build vehicles that are affordable only for the few undercuts one of the pillars upon which the industry rests.

And this for those who may be starting their careers, regardless of what their undertakings are:

“The short successes that can be gained in a brief time and without difficulty, are not worth much.”

Even in the age of TikTok, endurance matters.

Farewell.

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)

.1692800306885.png)

.1687801407690.png)